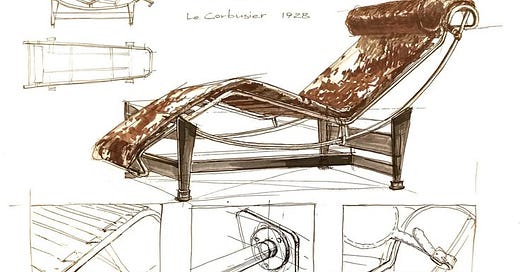

I used to want it, brown cowhide, clean lines, chrome frame. It is more than just a chair. It was is credential. I saw it on Frasier, in his bathroom of all places. It was the '90s. For me Frasier wasn’t just a fictional character on television. He represented a version of masculinity that turned away from sports and violence, and instead embraced design, art, and opera. It was power expressed through refinement. It showed that elegance wasn’t exclusively female. Because of that, Frasier shaped some of my early ideas about taste. As an effeminate boy, I saw in him a version of masculinity that gave me room to exist. It was all very aspirational to me.

The other day I realised that I could buy it now. But I won’t. Because over the years, I’ve come to detest it.

Not the aesthetic. Corbusier was a modernist visionary. The proportions are perfect. The restraint, the geometry, the coolness. They're all doing their job. But the job, as it turns out, was the problem. So why?

Because he didn’t love people

Le Corbusier didn’t love people. He loved the idea of people. That’s not the same.

Design, to him, wasn’t a way to express humanity. It was a way to overwrite it. He believed people could be improved. Not with food, safety, dignity. With angles. With grids. With straight lines and math.

He called houses "machines for living in," which sounds clever until you realise he meant it. He saw cities as problems of efficiency. People as parts. Streets as clutter. Differences as defects. So he built simple answers to things that were never simple.

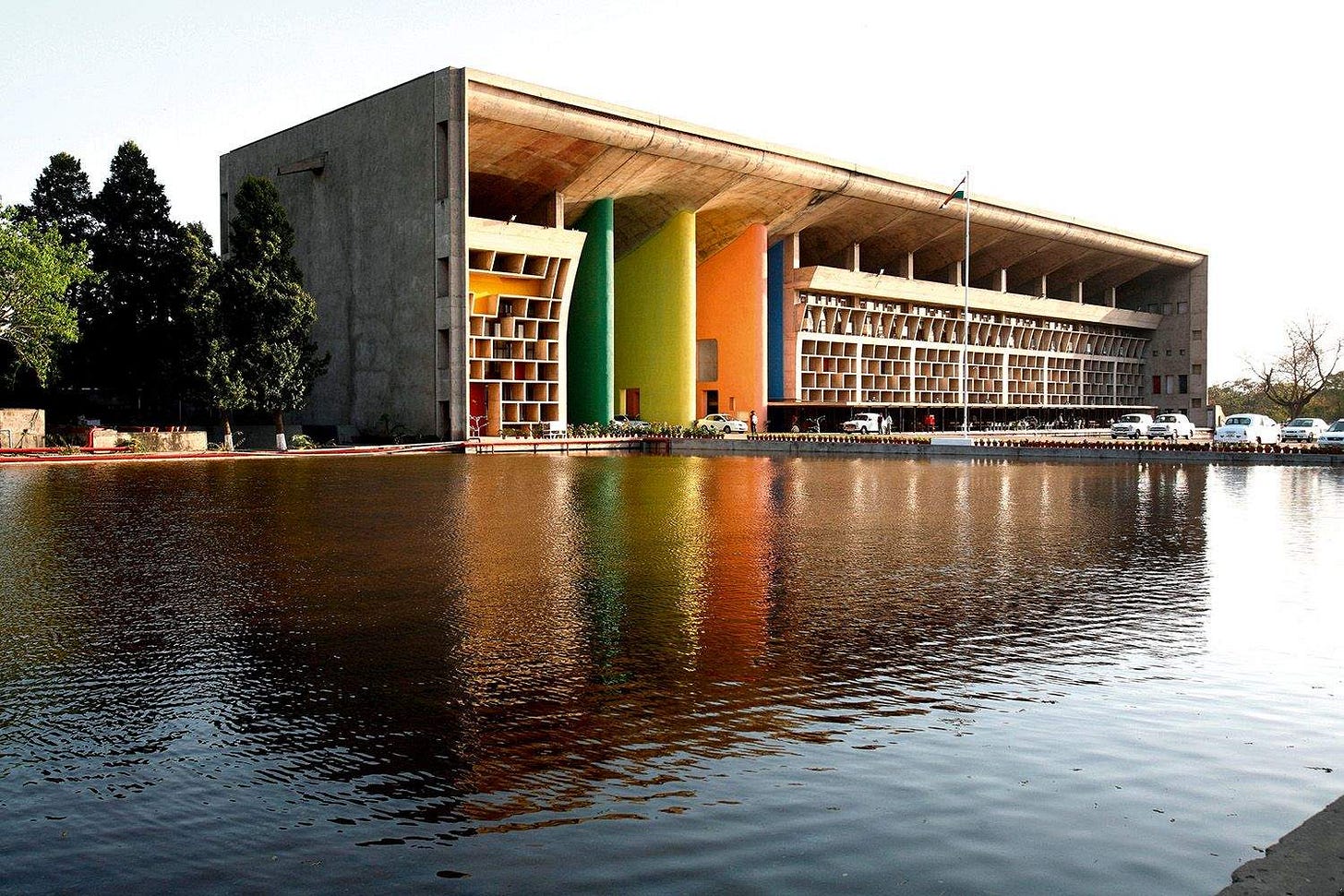

Chandigarh, his capital project in India, was meant to embody a rational utopia. What it delivered was an alienating grid, with no bazaars, no chaotic charm, no warmth. The people who lived there didn’t ask for it. It was a city built like a diagram. Judging by his idea of city planning, he wasn’t the kind of person who would sit at a terrace and enjoy watching people pass by.

Because his utopia was sterile

We’ve learned to mistrust the idea of utopia. Science fiction helped with that. Le Corbusier did too. He sold a vision so clean, so ordered, so detached from real life, it made utopia sound like a warning.

He tried to box life into labelled zones and compartments, to contain its messiness in concrete forms. In doing so, he stripped cities of the very things that make them human.

Chandigarh was praised on paper but felt alien in practice. A rigid, Eurocentric order. Monumental buildings. No bazaars. No spontaneous corners. No city noise. Just diagrams you could live in.

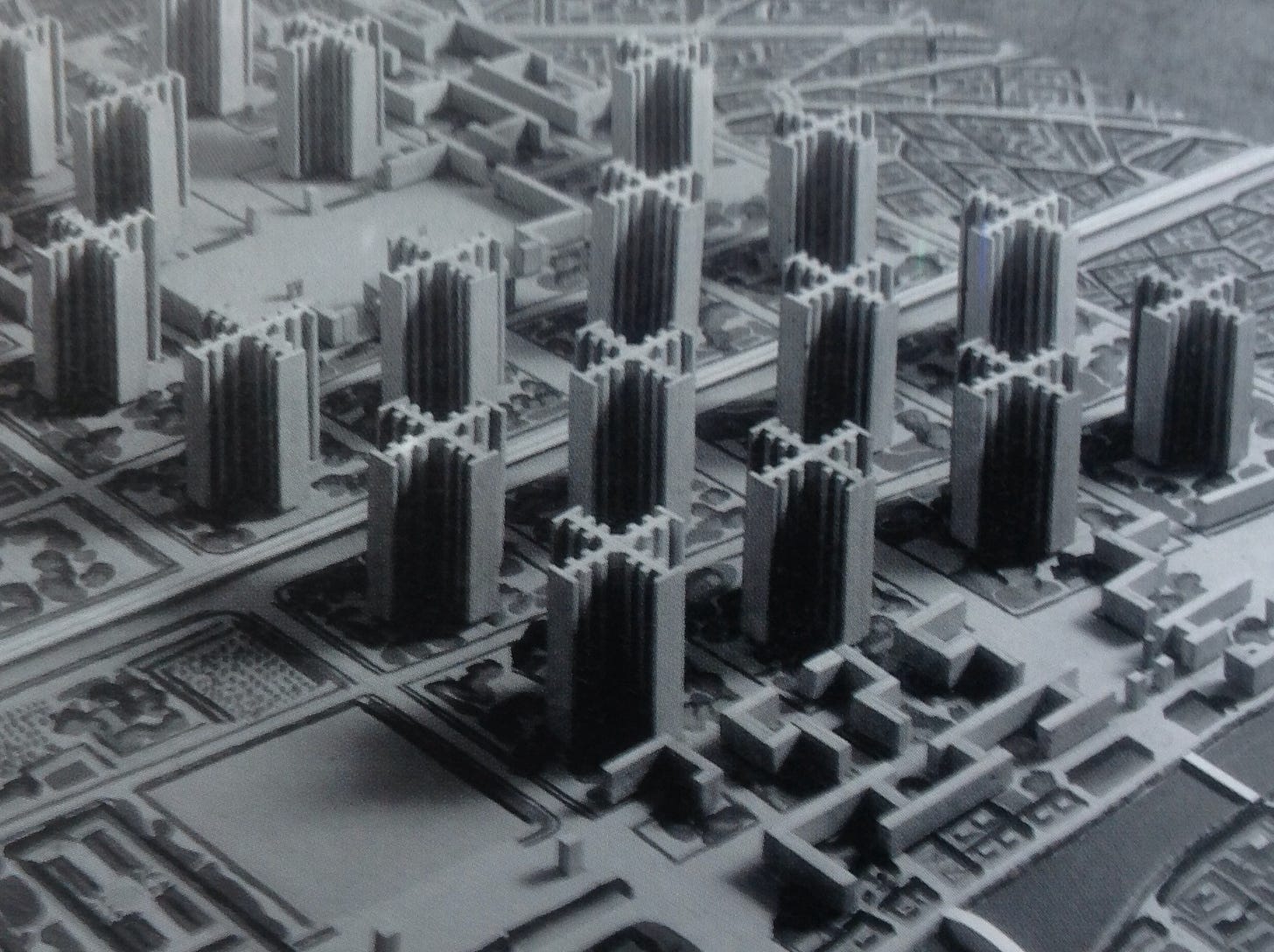

His broader vision, the Radiant City, took this further. It replaced vibrant streets with highways. Replaced neighbourhoods with towers in parkland. Called it progress. He declared "the death of the street" like that was a good thing.

But the open spaces he imagined became empty. In Marseille, the Unité d’Habitation’s raised ground level didn’t become a garden. It became a void. In St. Louis, Pruitt–Igoe, a housing project built in his image, ended in ruin, demolition, and the collapse of the community it was supposed to serve.

He feared complexity. He chose order over life. Geometry over unpredictability. But when you flatten everything into logic, you lose the friction cities need to live. Streets are where life happens. He forgot that.

Because his politics weren’t innocent

In the 1930s, in colonial Algiers, he imagined a future designed for Europeans only. His Plan Obus proposed a massive elevated highway and luxury housing for the colonisers, raised above the Casbah, where the indigenous population lived. It wasn’t urban improvement. It was segregation by design. His architecture literally elevated the coloniser.

At his softest, you could call him an opportunist. But one could also say it’s hard to find a totalitarian regime he didn’t flirt with.

And we should remember: he offered his talents to Stalin, Mussolini, and Pétain. He liked strongmen. Not because he loved politics, but because they might finally let him build his utopia.

During the Vichy years, a period from 1940 to 1944 when a Nazi-collaborating government controlled unoccupied France, he advised the regime. He believed order mattered more than disagreement. That visionaries should override democracy. He admired Mussolini’s Italy for getting things built. That was the bar.

You won’t find that on a museum plaque. At his softest, you could call him an opportunist. But one could also say it’s hard to find a totalitarian regime he didn’t flirt with.

Because he believed design should control people

He thought design could shape character. If you planned someone’s surroundings just right. By putting them in towers, sorting them into zones, sharpening the edges. He believed they’d behave better because of that.

He believed in environmental determinism. That the right buildings could make people act right. That citizens could be fixed by architecture.

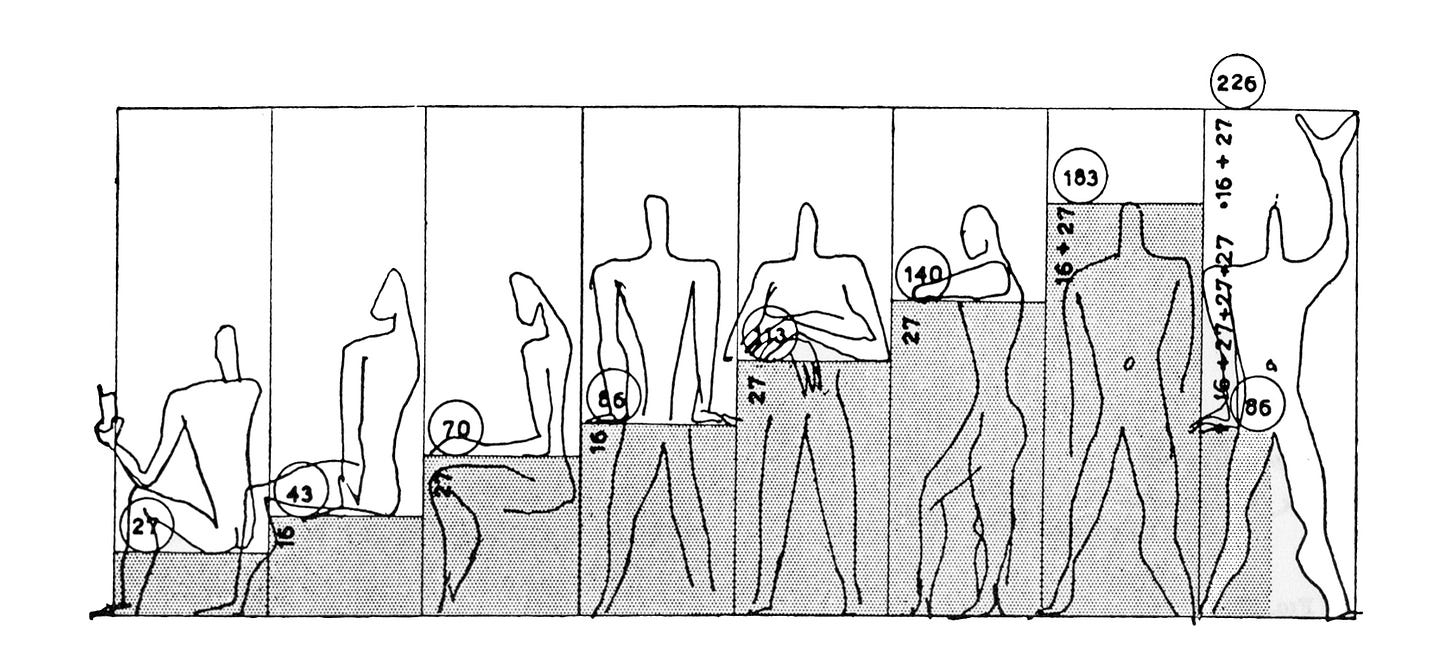

His Modulor, a fictional six-foot white man with his arm raised, was his measuring stick. He used it as a universal standard. Everyone else had to fit it.

But you can’t design your way out of difference. You can’t erase history with a grid. Every time someone tries, the result is a kind of aesthetic violence. It becomes too clean, too bright, too flat. Like living in a spreadsheet. Like forcing everyone into Helvetica.

Because I wouldn’t enjoy it

So no. I won’t buy the LC4

It feels like a trophy from a regime I don’t subscribe to. And the reasoning isn’t far off from why you might think twice about buying a Tesla these days.

All design can really do is express who we already are. And who we are is messy. Contradictory. Unbalanced. Loud in places. Quiet in others.

Chairs can’t change that.

And neither can Le Corbusier.

So, here you have it. This is how I rationalised saving money by not buying another chair.