Give us some head

Decapitations. Artists painted them, audiences stared, and let’s be honest, you stopped and are reading this. Masters could’ve painted heaven or lovestories, but no. The severed head always wins. It still makes the best thumbnail. And imagine being in the 18th century, hanging this above your fireplace, people would talk.

It’s not subtle. It’s not symbolic. It’s a showstopper. A sword to the chest is just noise. A sword to the neck? That’s cinema. Especially if they serve it on a silver plate.

We’ve already covered Medusa and Judith, legends in their own right. But the gallery of heads doesn’t stop there.

Here are six more, each capturing the moment when the story turns, whether it’s the act itself, or the silence that follows.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1609–10)

Saint John the Baptist was a fiery preacher who called out corruption including Herod Antipas’s scandalous marriage. That got him thrown in prison. Then came a party, a dance, and a deadly promise. Herodias, the queen, used her daughter Salome to ask for John’s head. And Herod, cornered by pride and politics, delivered.

Rubens doesn’t paint the quiet end he gives us muscle, motion, and blood. This isn’t martyrdom. It’s theatre. John is no longer a prophet he’s a symbol, about to be served.

Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath (c. 1610)

This isn’t just any beheading, it’s a confession. Caravaggio paints young David with Goliath’s severed head dangling, but the mood isn’t triumph. It’s haunted. Some say the head is Caravaggio’s own, a painter painting himself as the fallen.

By the time he painted this, Caravaggio was on the run for murder. And not just that one. His paintings are littered with death,Judith beheading Holofernes, Salome with John’s head, and now David holding his own guilt. Violence follows him, even on canvas. Especially there.

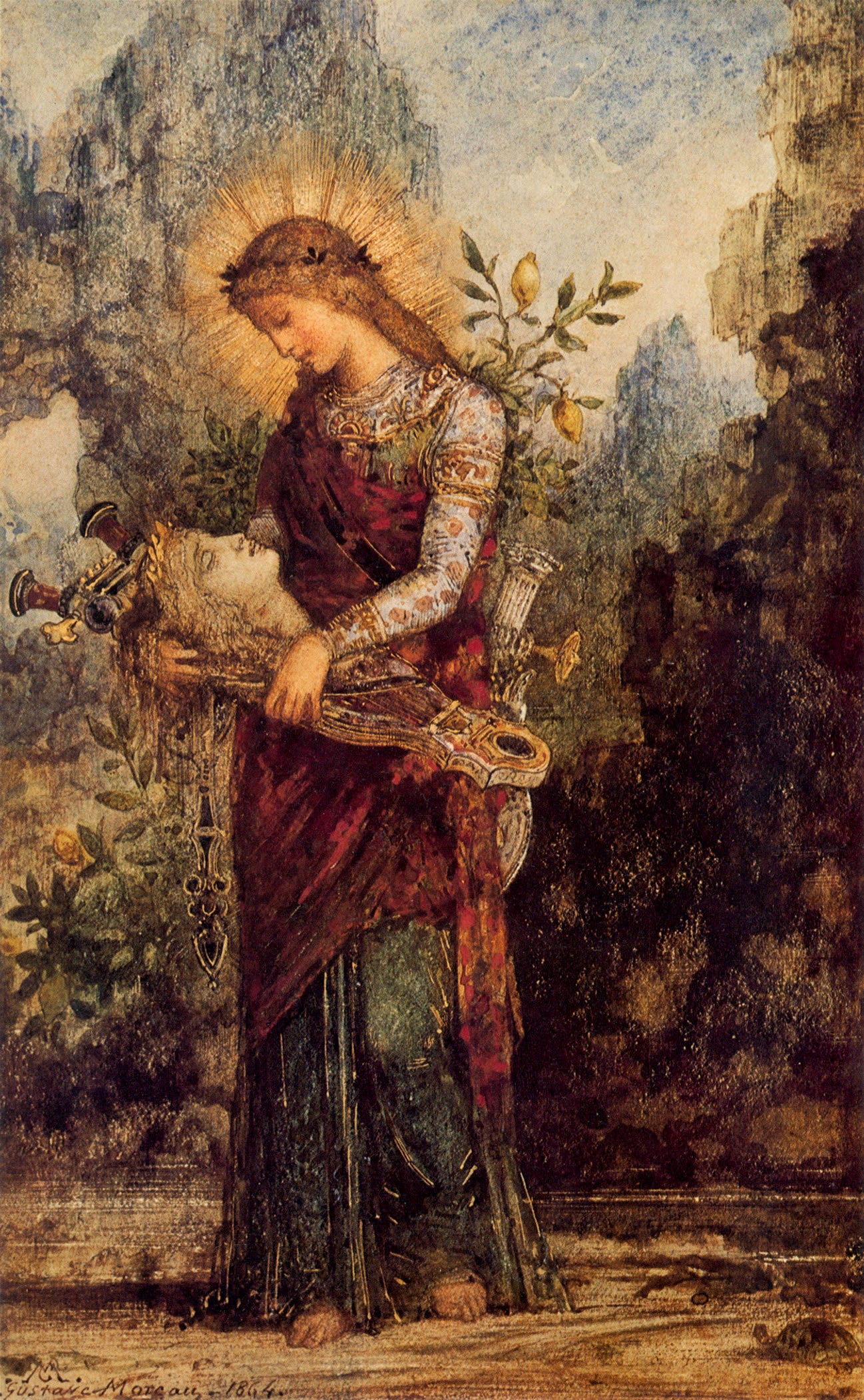

Gustave Moreau, Thracian Girl Carrying the Head of Orpheus (1865)

Here, the image is soft, almost tender. A girl cradles Orpheus’s severed head on a lyre, floating in melancholy moonlight. In the myth, Orpheus tries to rescue his beloved Eurydice from the underworld, fails, and retreats into song. The Maenads, enraged either by rejection or the power of his music, rip him apart. His head floats downstream, still singing.

Moreau, a Symbolist, isn’t interested in the gore. He paints the afterimage, the calm after chaos. This isn’t blood and madness. It’s loss, beauty, and myth that won’t let go. The girl? She could be grief. Or the echo of Eurydice. Or the last person who still hears him.

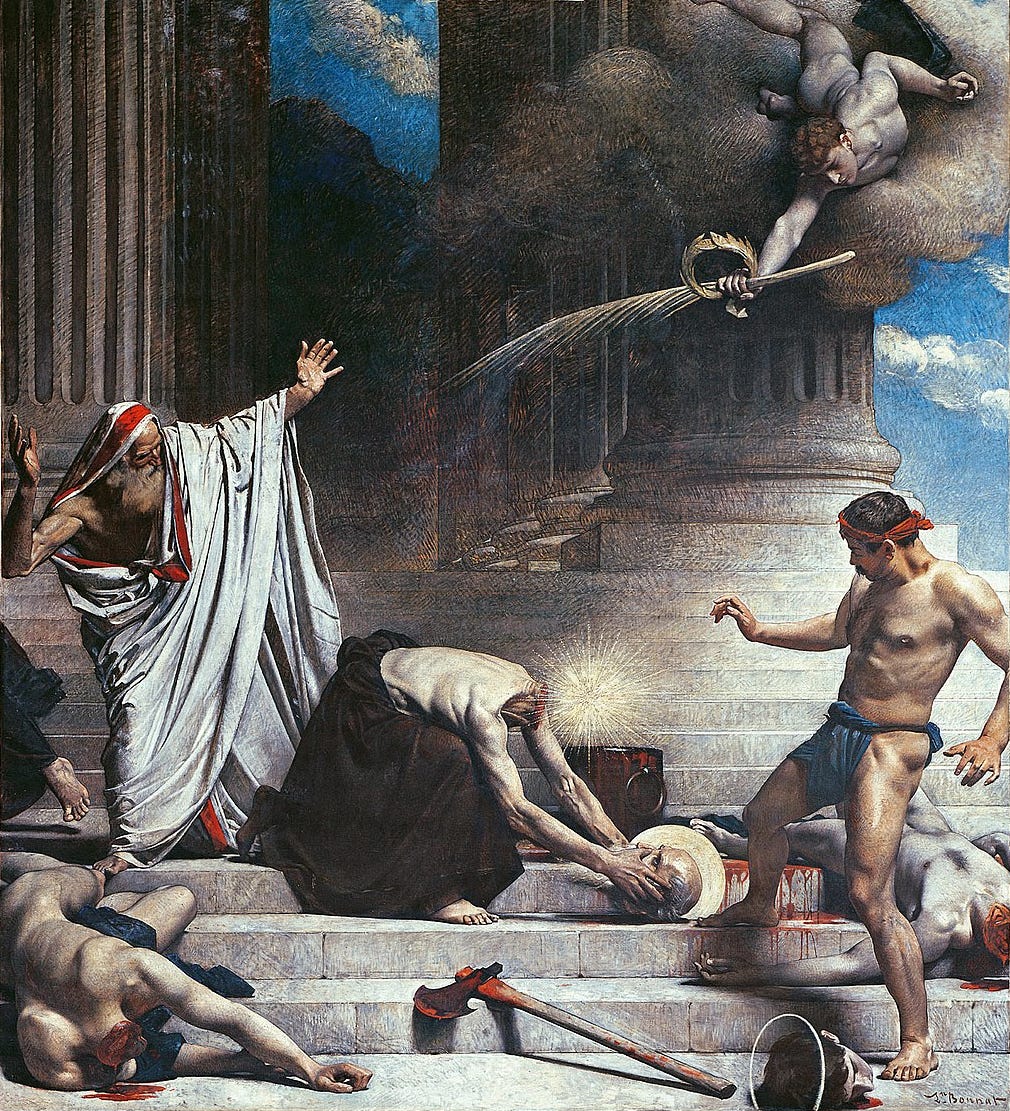

Léon Bonnat, Le Martyre de Saint Denis (c. 1870)

Saint Denis is the patron saint of Paris, but what makes him unforgettable is what he did after his execution he picked up his own head and walked. This canvas captures it all misty light, Roman soldiers, and a bishop calmly carrying his skull like it’s a travel accessory. Saint Denis, after being executed for spreading Christianity in Roman-occupied Gaul, didn’t just die he walked. According to legend, he lifted his head, gave a short sermon, and calmly carried it several miles to the spot where he wanted to be buried. That’s not just martyrdom. That’s brand management.

Bonnat leans into the miraculous as something almost anatomical blood, bone, fabric, and faith, all rendered with eerie precision. Saint Denis just walks it off, head in hand, like it's the most normal thing in the world.

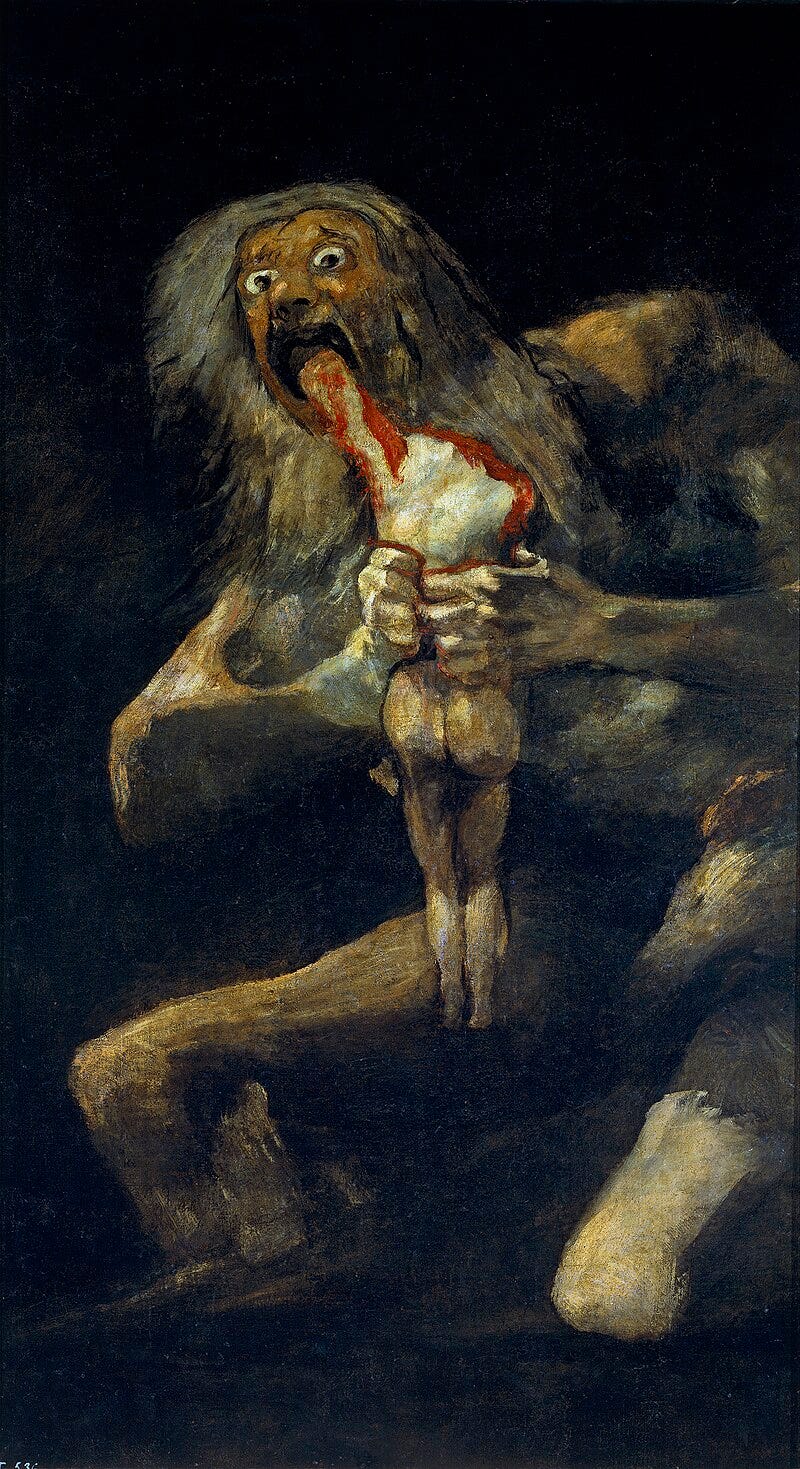

Francisco Goya Saturn Devouring His Son (c. 1819–23)

Okay, not a traditional beheading, but close enough. Saturn is mid-bite, holding the half-eaten corpse of his son, eyes wide with madness. There’s no elegance here. Just raw, terrifying hunger.

Painted directly on the walls of his house, this was Goya in full breakdown mode deaf, isolated, politically disillusioned. Saturn’s act isn’t just myth; it’s the collapse of reason. A warning. A scream. Maybe even a self-portrait of Goya as a country eating itself.

Théodore Géricault Têtes de Suppliciés (c. 1818–19)

These are real heads. Severed, guillotined, freshly dead. Géricault painted them while researching The Raft of the Medusa, borrowing from morgues and executioners. But these heads became their own project raw studies in death, decay, and uncomfortable beauty.

What kind of artist spends days sketching beheaded criminals? One obsessed with realism. One who knows that you can’t fake tragedy unless you’ve stared into its literal eyes. These heads don’t tell a myth. They tell the truth, and it’s not poetic. It’s clinical. And somehow, it’s still hauntingly human. And if you're brave enough, you can see where it all led check out Géricault’s final painting The Raft of the Medusa where the dead don’t just stare back They drift. They haunt.

Epilogue

Before the French Revolution, losing your head was an honour reserved for the powerful. After 1789, égalité meant everyone got a turn. It wasn’t just execution, it was erasure. A public act of silence. That’s why kings, saints, and prophets so often end up headless in paint.

Even in Greek myth, the head is the final word. When Achilles hears of Patroclus’s death, he screams out that it is as if he’s lost his own. Killing Patroclus wasn’t just an attack, it was an attempt to silence him and his troops.

And speaking of Patroclus and Achilles, let’s go back to giving head. It’s poetic, sure, but also a way to be silenced. Don’t think too hard about that.