Lovers become trees. Liars become stones. Gods become animals or clouds or light. And at the center of it all stands Zeus, who changed shape more deliberately than anyone else. Sometimes because he was clever. Often because he was horny.

At the surface. He did it for desire. For beauty, for proximity, for legacy. Sometimes to get closer. To slip out before things got complicated. He seemingly shapeshifted to bypass resistance. To avoid Hera, the wife. He just wanted what he thought he couldn’t have.

These stories are sharp-edged. Desire dressed as lies. Lust framed as legend. Deception. Abduction. Disguise. Things taken without asking. The beauty of the masterpieces only makes it easier to look.

Here are seven stories of the god who needed to change into lesser things to get what he wanted.

The softest way to steal a girl

The abduction of Europa, Jacob Jordaens, c. 1643

Zeus doesn’t show up thundering down from Olympus, ready to impress. He becomes a bull. Calm. White. Beautiful. Not just safe but inviting. The kind of body you’d reach for without thinking. He chooses softness because it draws her in. He wants her to touch him. To climb on. And she does. Just long enough for him to carry her off.

Jordaens paints the pause before everything changes. Europa still smiling. Still trusting. Still dry. Then the sea. Then the myth. She ends up in Crete, the mother of a future king. Their son is Minos. The bull disappears. The story does not.

When beauty hatches chaos

Leda and the swan, Antonio da Correggio, c. 1532

Zeus wants closeness. So he becomes grace. A swan. Smooth feathers. Clean lines. A body designed to slip past alarm. Grace made flesh. Something elegant enough to be trusted and just strange enough to feel like fate. Correggio paints serenity. But the myth doesn’t feel serene. The seduction is murky. The transformation is strategy.

Leda lies with the swan. She also lies with her husband. Two eggs follow. From one, Helen. From the other, Castor and Pollux. The twins will become heroes and take their place in the sky as Gemini. Helen will become a cause. Her beauty will launch a thousand ships and ignite a war. Her story doesn’t live in the stars but in the poems, plays, and ruin of Troy.

When pure desire found its perfect form

Danae, Gustav Klimt, 1907–1908

Danaë is locked away by her father who is afraid of a prophecy. The child she bears will end his life. So he seals her off.

Danaë is the kind of beauty no one was meant to have. That was part of the point. She was meant to be admired, not touched. But Zeus doesn’t handle distance well. He doesn’t knock. He becomes gold. Not just wealth or light but pure desire in its most persuasive form. Something dazzling enough to slip through walls and saturate whatever it touches. Klimt paints her mid-surrender. Hair curling, limbs folding, gold spilling between her legs. From that shimmer comes Perseus. The slayer of Medusa and saviour of Andromeda. Another legacy, poured through a crack. We’ve told his story before, surrounded by other masterworks.

Olympus wanted a toyboy

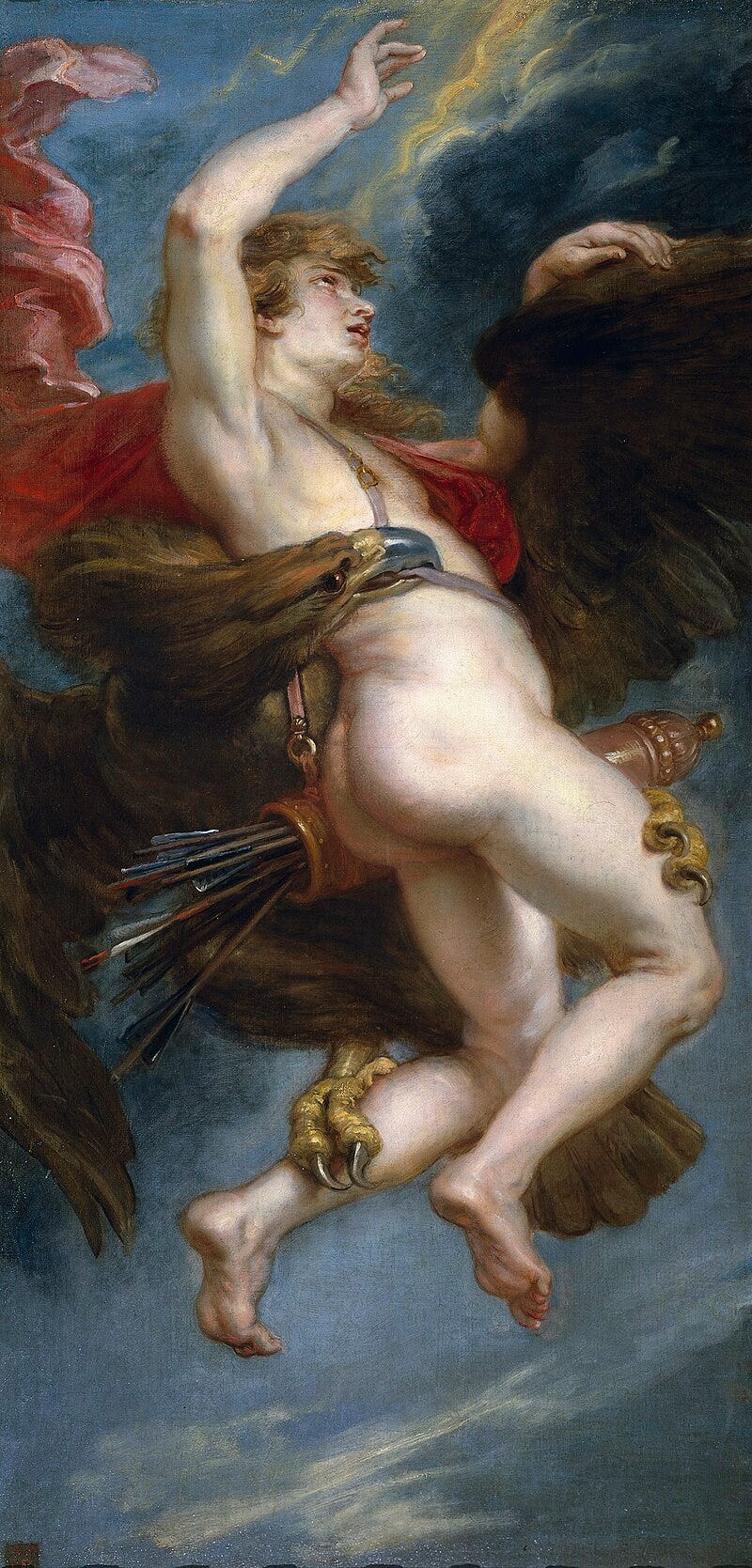

The abduction of Ganymede, Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1638,

Zeus sees Ganymede and is overtaken by pure gay desire. He transforms. No mist. No disguise. Just an eagle with claws and a mission. He lifts the boy into the sky. Rubens captures him midair. Legs flailing. Face unsure. Somewhere between being chosen and being taken.

Ganymede is brought to Olympus. He gets immortality. A job. A seat near the gods. And Zeus gets something to touch. To admire. To fantasise about. Ganymede sparkles but does not speak. He pours ambrosia, the drink of the gods. He serves. He glows in orbit. A celestial toyboy in divine suspension. A reminder that power can rename possession as romance.

It’s a queer theme that never needed a code. It was out there for all the people to know. A boy, a god, and a look that lingered too long. That’s why it featured in the queer art history article on this blog.

When desire is in the air

Jupiter and IO, Antonio da Correggio, c. 1530

Zeus watches Io. The beautiful mortal priestess of Hera. Hera watches Zeus. So Zeus becomes mist. He wraps himself around her. Intimate. Inescapable. He becomes air with intent. Correggio paints it soft but close. Afterwards, to hide what happened, Zeus turns Io into a cow. Not out of mercy, but out of fear. The kind of fix that smells like a celestial NDA without agreement part. She doesn’t get safety. She gets horns.

She wanders. Horned. Silent. Watched. Until she reaches Egypt, where Zeus changes her back. Not with regret. With timing. Her suffering isn’t undone, it’s reabsorbed. Her pain repurposed for mythic glory. She becomes part of something bigger. Her line leads to Heracles, the half-god hero whose strength would outshine the pain that made him possible.

Drama you can see on clear nights

Jupiter and Callisto, François Boucher, c. 1744

Callisto is loyal to Artemis. Her vow is no men. No touch. No exceptions. Zeus sees her, another love he wasn’t supposed to have, and becomes her goddess. Not metaphorically. Not in spirit. He takes on Artemis’s form. Familiar. Safe. Trusted.

Boucher paints the unraveling. A hand where it shouldn’t be. A gaze that lingers too long. One breast already bare, not for beauty, but for foreshadowing. From that breach comes Arcas. Years later, while hunting, he almost kills a bear, his mother, changed and unrecognised. The gods stop him just in time. They place them in the sky. Callisto becomes Ursa Major. Arcas becomes Ursa Minor. The Great Bear and the Little Bear. Mother and son, orbiting forever, never quite touching. Try to think of that drama next time you look up.

Too weird to paint, but he still got the girl

A bug’s life, pixar c. 1998

No known artwork. Still waiting for someone to paint it. Maybe because the story is too small, too strange, too embarrassing. A god becomes an ant to creep in. Not mighty. Not seductive.

Eurymedousa is approached. She’s a mortal woman, tucked somewhere off the path of Olympus’s usual dramas. Not royal. Not radiant. Just ordinary enough to be overlooked. And maybe that was the draw. Zeus didn’t need to conquer a goddess this time, just someone who wouldn’t see it coming. A god wouldn’t get close. Too much presence. Too much power. But an ant? That could crawl in unnoticed.

From that encounter comes Myrmidon. His descendants will fight beside Achilles in the Trojan War. The absurdity lingers. A god becomes an ant and spawns a lineage of soldiers.

How far we bend to be wanted?

Zeus didn’t shapeshift to grow. He shapeshifted to get in. Every form he took was a tactic. A trick. A softer version of the same plea: Do you want me now?

He didn’t change out of love. He changed out of want. Out of fear. Out of that doubt that even the king of gods might not be enough.

That doubt lingers. We've all felt it. The quiet question: Am I enough for the one I want? So we shift. We adjust. We perform. All of us editing ourselves in real time, just sharp enough to catch someone's eye. Just soft enough to be wanted.

And maybe that’s why artists keep painting it. Because of this shapeshifting we do every day. What we wear. How we laugh. The way we step into a room. It's just a mortal remix of the same instinct. We adjust. We suggest. We disappear into a version we hope will be wanted. Little lies. Little seductions. Little abductions. Zeus just did it louder.

In the end, desire doesn’t just move the gods. It reshapes us. Quietly. Constantly. So what are we without desire?