Samson is the Old Testament’s very own Greek tragedy

We’ve spent enough time in the orbit of Greek myth, with its half-gods, feuding deities, and their soap-opera level antics. Now, let’s take a detour into the Old Testament, where the stakes are higher, the romance is thinner, and no one ever just “has a good time.”

Which brings us to Samson.

If you squint, Samson looks like a Greek hero. He’s a supernaturally strong warrior, his enemies fall before him in absurdly high numbers, and his story involves a beautiful woman, betrayal, and a tragic downfall. But don’t be fooled, this isn’t Achilles throwing a tantrum or Odysseus outsmarting gods. The Old Testament isn’t into playfulness. Samson’s story is grim, raw, and laced with an inescapable sense of doom.

And yet, he is one of the most visually represented figures in religious art. A character so epic, so violent, so tragic, that painters couldn’t resist putting him on canvas. From Rubens to Rembrandt, from Renaissance to Romanticism, Samson was a muse for brutality and betrayal.

So let’s begin. A man with the strength of a god. A woman with the power to undo him. And an ending so brutal it makes Greek tragedies look like a sitcom.

The Prophecy, A child of strength, born under divine contract

The announcement of Samson's birth, by Matthias Stom, c. 1630-1631.

It starts very Greek, with a prophecy. A barren woman, an angel, and a divine decree: “You will bear a son. But there are rules.” No drinking, no haircuts, no breaking the sacred vow. Basically, the child would become a toddler with godlike strength and a lifetime ban from barbershops. Samson is born already under contract, a walking prophecy wrapped in baby blankets. His parents probably had no idea they were about to raise ancient Israel’s first and only superhero, a man whose strength was legendary, but whose life choices would make reality TV contestants look responsible.

When you’re so strong, weapons are optional

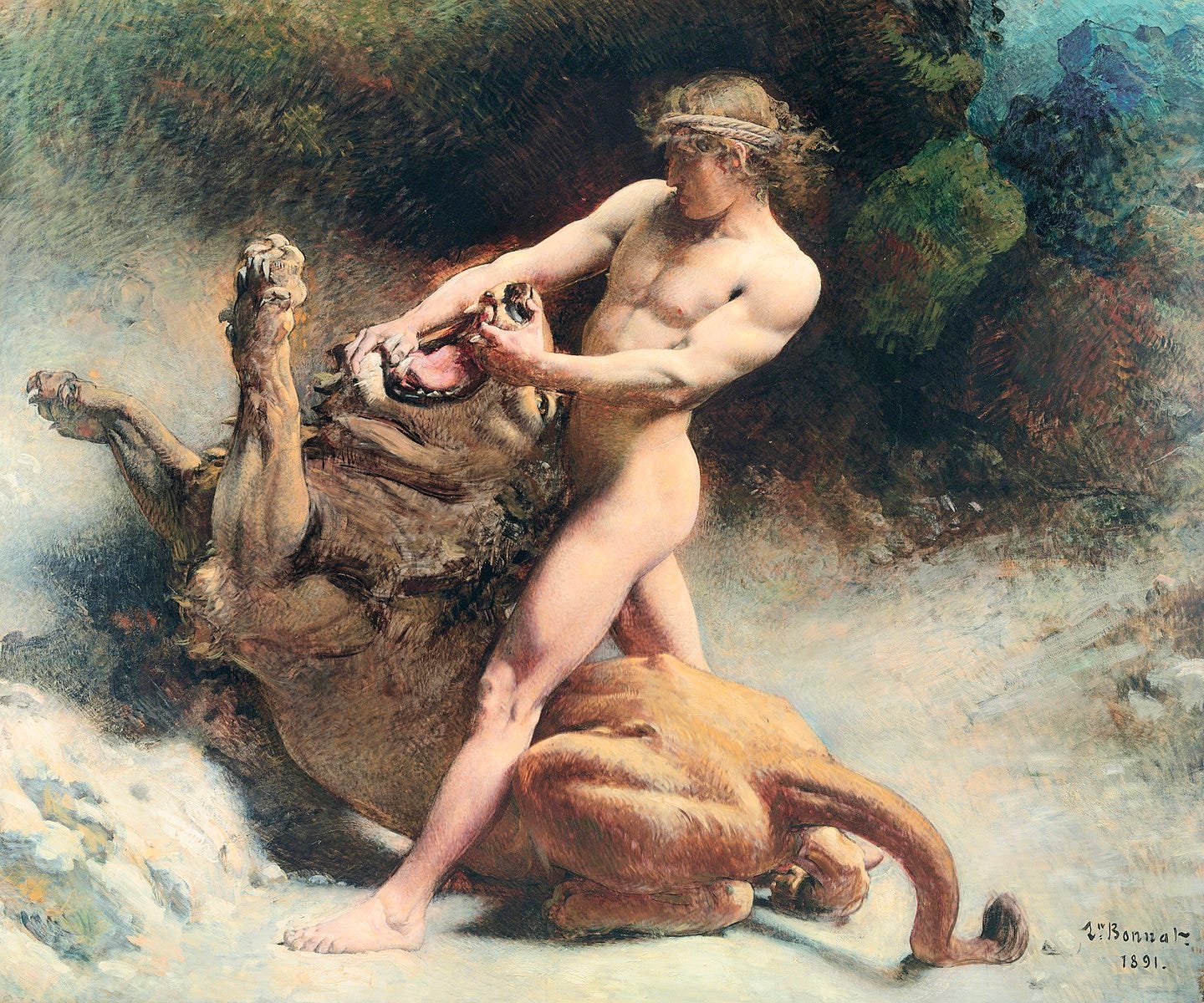

Samson's youth, by Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat 1891

One day, Samson is out for a walk when a lion jumps out at him. Now, most people would scream, run, or at least grab a weapon.

Not Samson. Violence is his first language.

He just grabs the lion with his bare hands and rips it in half like it’s a loaf of bread. No weapons. No hesitation. Just raw, terrifying strength. Then, a few days later, he comes back and finds a beehive inside the lion’s carcass. Naturally, he eats the honey. Because, of course, that’s what you do when you see bees nesting inside a decomposing predator you murdered. This will come up later. Trust me.

His father, did not know of any of this but he had many questions about his son. Chief among them: "Why is my son like an impulsive brute? Couldn’t he have picked up a book instead?"

A wedding, a riddle, a betrayal, a massacre

The wedding feast of samson by Rembrandt, 1638

Samson decides to marry a Philistine woman (not a great choice, considering the Philistines are public enemy #1 in Israel). His father, Manoah, is less than thrilled. He probably envisioned his son settling down with a nice Israelite girl, maybe one who wouldn’t inspire him to kill people over riddles. But no, Samson, as always, follows impulse over wisdom. At his wedding feast, he makes a bet:

“Solve my riddle, and I’ll give you 30 sets of clothes. Fail, and you give me 30.”

The riddle? A callback to his lion-killing spree:

“Out of the eater, something to eat; out of the strong, something sweet.”

(It’s about the honey inside the lion, which, let’s be real, no one could possibly guess.)

The Philistines, furious, force his new wife to extract the answer from him. She does. And as will become a common theme in Samson’s life, betrayal leads directly to murder. They solve the riddle. He loses the bet.

His response? Violence.

Murders 30 random Philistines, steals their clothes, and storms off.

The wedding is over. His wife, understandably, moves on. Samson, already an emotional wreck, gets worse.

When everything can be a weapon

Victorious Samson, by Guido Reni 1614-1616. Guido Reni

In the aftermath of the wedding, the bride was given to the best man. Another Philistine betrayal, Samson's grief turns to unchecked rage. He sets their crops on fire, escalating tensions to full-blown war. The Philistines try to capture him. Huge mistake.

Now comes a scene no action movie director should ever dare to remake, the brutality reaches epic new levels. Samson looks around, grabs a donkey’s jawbone, and proceeds to kill 1,000 men with it. Just swings away like he’s at some horrifying version of a batting cage, except instead of baseballs, it’s an army of Philistines getting obliterated.

No sword. No shield. Just a discarded skull and an ungodly amount of rage.

If any Greek hero had pulled this off, we’d have a constellation named after him

Enter Delilah, the ultimate femme fatale

Samson and Delilah by Anton van Dyck 1628

Enter Delilah, the most famous betrayer in history not named Judas.

The Philistines bribe her to find out how to take Samson down. And so begins one of history’s most excruciatingly predictable con jobs. Delilah pesters him relentlessly, baiting him with the kind of over-the-top, tragic wailing that could make a Shakespearean tragedy look restrained. He dodges. He lies. He deflects. First, he says fresh bowstrings will do it. She ties him up. He breaks free. Then, new ropes. Same result. Then, braiding his hair into a loom, which, frankly, sounds more like a Pinterest fail than a security measure. Every time, he shakes off the trap like it’s nothing.

Why does he keep playing along? The Bible doesn’t explain, and honestly, it doesn’t need to. A man as virile, powerful, and arrogant as Samson wasn’t thinking with his long-term survival instincts. Arrogance and horniness: a deadly combination.

Finally, Delilah wears him down. He caves:

“It’s my hair. Cut it, and I’m done.”

And so, while he sleeps, snip, snip, snip, his strength vanishes.

The strongest man in history wakes up helpless.

Samson and Delilah by Rubens 1610

Bound, Blinded, Broken

The Blinding of Samson by Rembrandt 1636

The Philistines seize him, gouge out his eyes, not swiftly, not mercifully, but with hot iron rods, a method so gruesome it barely needs embellishment. Not just because they hate him but because they want to turn him into a living symbol of their victory. He humiliated them. Now it’s their turn.

This is the part in a horror movie where you hold a pillow in front of your face. Poor Samson, blinded, stumbling, utterly broken. The invincible warrior turned into a public spectacle, dragged through the streets for everyone to see. But the Philistines aren’t just here for cruelty, they’re making a point. No one humiliates them and walks away, not even the man who once tore apart a lion with his bare hands.

From warrior to beast of burden

Samson and the Philistines by Carl Bloch, 1863.

The Philistines don’t just defeat Samson they break him. The once-great warrior, feared for his strength and unpredictability, is now blind and bound, sentenced to a humiliating existence grinding grain in a prison mill. He had once killed a thousand men with a donkey’s jawbone, and now? Now he’s the donkey. Shackled to a grindstone, trudging in circles, day in, day out. A living mockery of what he once was.

And if you think this is the end, wait. It gets worse. What the Philistines don’t notice is this: his hair is growing back.

Samson’s final, fatal encore

Samsons Rage by Johann Georg Platzer 1740

During a massive Philistine feast, Samson is paraded out like a trophy, a relic of his former self, mocked, humiliated, and put on display for the amusement of his captors. The crowd laughs, jeers, throws things. And there, in front of him, stands Delilah.

Placed between the temple’s two pillars, his hands bound. Perhaps he pulls his arms together, not to free himself, but in some desperate, final attempt to reach Delilah, the woman who betrayed him. His love for her had been endless, but his strength? Even more than that.

He prays for strength one last time.

And then, It breaks.

The entire temple shudders. The crowd freezes, their laughter cut short. Then, in a deafening roar, the pillars crack, the walls cave in, the ceiling collapses. Dust, screams, chaos. The greatest of the Philistine rulers are crushed beneath the weight of their own gods, Samson included. The feast turns to carnage.

This painting of this moment was the reason I went down this rabbit hole in the first place. When I first saw it in a museum (Belvedere in Geneva) , I stood frozen, convinced the pieces might fall and bury me too. The sheer weight of it, of Samson’s final act, of the temple’s collapse, of the whole story, felt immediate, like it wasn’t a relic of the past but something still happening, right there in front of me.

Epilogue: The weight of rubble

Samson’s story is not about redemption. It’s about power, arrogance, betrayal, and revenge. A warning, perhaps, about the cost of raw strength without wisdom, the blindness of love, the thin line between hero and destroyer. And perhaps this is why he is a one-of-a-kind in the bible.

What started as a Greek myth, with a prophecy, a divine birth, and a muscle-bound hero, did not end very Greek.

There were no gods to turn his tears into flowers, no divine chariot to carry him to the stars, no mountain bearing his name. No, this is the Old Testament, where tragedy isn’t poetic, it’s brutal.

Samson just left rubble. His final weapon wasn’t a sword or a bow, but the temple itself, his own death the only way to claim victory. The only way to end this was to end Samsom himself.

In the end, he goes out exactly as he lived, with chaos. And a body count.