It started with Patroclus. I was trying to draw one moment, the loss, the silence, the part after the battle, the anger and suddenly I wasn’t in the Iliad anymore. I was somewhere else entirely in a browser with 50+ tabs, all about death.

A Byzantine chapel. A Flemish altarpiece. A sugar sphinx melting in a factory. I had fallen into the long history of lamenting in art. In order to do research for my own work, I wanted to know how painting pain evolved over the years. The body. The witnesses. The space left behind.

Pain is pain, the only thing that changes is how we look at it. Once, lamentation was proof of divinity. Now it’s proof that someone cared. Once it was iconography. Now it’s biography. We used to ask why people died. Now we ask what it does to those who stay.

Before lamentation the divine didn’t flinch

Before lamentation, Christian art was more about theology than trauma. Christ didn't suffer, he posed. Eyes open. Arms out. Alive on the cross like he was mid-sermon. It wasn’t a scene of pain, it was a diagram of redemption.

Then, something cracked. Around the 11th century, Mary stopped kneeling. She collapsed. John wept. The angels twisted mid-air. Suddenly, pain was allowed in. Emotion entered the frame.

And just like that, the divine started looking disturbingly human. Which meant we started seeing ourselves in it.

A thousand years of grief, in ten pictures

11th–13th c. From icons to empathy

The Crucifixion scene in the Stavelot Missal (Monastic artists, c. 1090) still holds back emotion, but by the 12th century, Byzantine artists are letting it through the cracks. In a fresco in the Church of Saint Panteleimon in Nerezi, Mary presses her cheek to Christ’s face. John clutches a lifeless hand. Angels twist in midair. For the first time, we see holy sorrow as human sorrow.

fresco in the Church of Saint Panteleimon in Nerezi (Anonymous Byzantine artist, c. 1164)

Cimabue’s Crucifix pushes it further-Christ’s body slumps, dead weight hanging from the wood. It’s not beautiful. It’s painful. And it sets the stage for what comes next.

Cimabue’s Crucifix (Cenni di Pepo, c. 1265–1270)

14th–15th c. Drama enters the frame

With Giotto’s Lamentation, lamentation becomes a real scene. He gives his mourners back their bodies and their grief. They gesture. They collapse. You can feel the weight of Christ’s corpse in their arms. It’s choreographed but never artificial.

Giotto’s Lamentation (Giotto di Bondone, 1305)

Rogier van der Weyden takes that grief and polishes it like glass. His Descent is a study in choreography. Mary’s collapse mirroring Christ’s body, every gesture part of a sacred script. But behind the precision is something deeply human. It tells us that even stylized grief can hit like truth. It’s theatrical sorrow that doesn’t fake it, it performs pain to make it real.

Descent from the Cross (Rogier van der Weyden, c. 1435)

16th–17th c. The beautiful dead

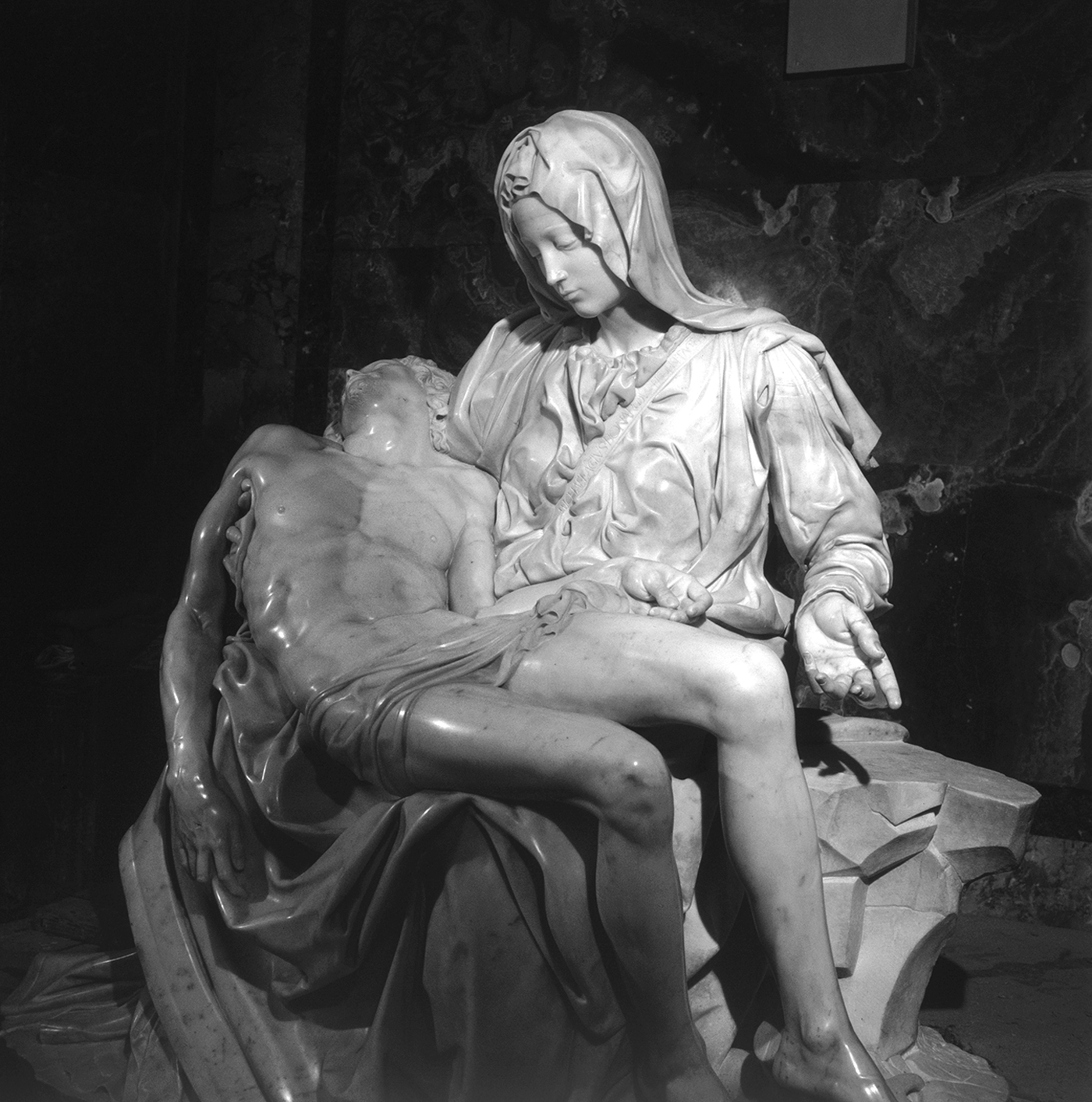

Michelangelo’s Pietà is quiet. Sublime. Christ rests in Mary’s lap like marble folded into itself. No screaming. Just serenity. As if lamentation has now learned to be noble.

Pietà (Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1498–1499)

Caravaggio, by contrast, brings it back to earth. In The Entombment of Christ, the body is heavy. The tomb is real. The people are exhausted. And the light? Divine spotlight on human failure. This is not symbolic. This is what it’s like to carry someone you love into the dark.

The Entombment of Christ (Caravaggio, 1603–1604)

18th–19th c. Mourning without miracles

Benjamin West does something strange in 1770. He paints a general’s death, like a pietà. Redcoat instead of robe. Battlefield instead of Calvary. He turns pain into politics, mourning as statecraft. Wolfe’s death becomes a nation’s moral centerpiece. This is lamentation used for power, a public cry scripted to shape collective memory.

The Death of General Wolfe (Benjamin West, 1770)

Then Gustave Courbet arrives, and throws the whole myth out. A Burial at Ornans is a funeral stripped of spectacle. The priest barely holds your eye. The mourners look tired. A dog wanders in the frame. This is grief as it happens, imperfect, earthbound, social. It tells us that pain doesn’t have to be poetic to be true. Sometimes lamentation just means showing up.

A Burial at Ornans (Gustave Courbet, 1849–1850)

20th–21st c. From protest to reckoning

Then came Pablo Picasso, and Guernica The bombed town. The flattened woman. The child clutched in a howl. This isn’t mourning—it’s chaos. Pain here doesn’t resolve. It fractures. Guernica doesn’t guide you to feeling; it detonates it. A scream with no mouth. Lamentation as an act of war against war.

Guernica (Pablo Picasso, 1937)

And finally, Kara Walker’s A Subtlety. A sugar sphinx mourning slavery in a condemned refinery. Kneeling. Enormous. Melting. Its grief made monumental and fragile. Her presence accuses. Her silence roars. This is lamentation that refuses to be tidy, one that names pain that was never mourned. A reminder that some wounds aren’t healed, they’re just finally noticed.

A Subtlety (Kara Walker, 2014)

Epilogue Where do we go from here, Patroclus?

Right now I’m trying to figure out what Patroclus’s death did to Achilles and whether what I’m working on is even a lamentation or just the moment where spite gave way to wrath. There’s no clear answer. Which is probably why I’m still here, looking at all these images, trying to make sense of how grief looks when it can’t be contained.

However, these artworks remind me that we don’t always need resolution in art. Sometimes it’s enough just to stay with the dead for a while. To be with those who are left behind. To remember that mourning is not weakness, it is power.

And across a thousand years, these images keep trying to show us, this hurts. And it builds something. Maybe not peace. But a kind of clarity. That’s what I’m after. Not closure. Not catharsis. Just the strength to name the wound and keep moving.